–

If you read “Unbreakable”, the memoir by former world No. 4 Jelena Dokic, when it came out in 2017, you were shaken to the core.

It seems “everyone knew” something was going on. But no one did anything about it. Or couldn’t. And the abuse she suffered at the hands of her father Damir was almost beyond description.

Two days after the end of this year’s Australian Open, where Dokic was a prominent presenter and interviewer on host Channel 9, those memories returned – and then some – with the airing of a new documentary.

It was one thing to read the words. Watching her talk about it, listening to the large group of people around tennis offering their thoughts, must have felt like reliving it all over again for Dokic. And for those familiar with her story.

The one-hour, 40-minute documentary aired on Channel 9 on Wednesday night in Australia. And it was promoted during the fortnight of the Australian Open. Although, noticeably, whenever those promos came on and Dokic was on air, they were greeted with silence.

With a renewed focus on the health and safety of the young women on the WTA Tour in the wake of the Elena Rybakina saga, it’s worth digging into this story once again to see how horrific the worst-case scenario can be – the most cautionary of cautionary tales.

(All screenshots from the documentary “Unbreakable”, airing on Australia’s Channel 9).

Where to begin …

Dokic’s memoir, it turns out, only could scratch the surface of the terror she went through.

The addition of video, and photographs, and some emotional testimony from tennis figures who were around her in those early years just make it even more harrowing.

Dokic herself, now still just 41 and recalling events that occurred a lifetime ago, was remarkably composed for most of it. But for the very worst of it, you could see that it was all coming back to her as if it had happened just yesterday.

By 1991, with Yugoslavia in the midst of a deadly civil war, the Dokics just packed up and left Croatia for Sombor, Serbia one day. The clothes on their backs, Seven-year-old Jelena’s racquets. Not much else.

And the pressure intensified.

“I woke up (every morning and asked myself); “How do I make sure he doesn’t hurt me today? No matter how hard I worked on the court, it was never good enough for him. I found the verbal abuse just as hurtful: Cow. Bitch. Dumb. Useless,” Dokic recalled.

They were refugees now. “The family’s future is on my shoulders, in my hands, because of tennis,” she said.

(This refrain, from so many young women with ambitious fathers who come from modest beginnings and put everything they have into their daughter’s tennis success, is all too common. And too often, it leads to disaster).

By 1994, they were refugees again – this time in Sydney, Australia. Jelena didn’t know a word of English. Damir had started drinking.

She was 14 when she won Traralgon, the big tuneup event for the Australian Open juniors. The next week, she lost in the second round. “Back to the hotel. He was abusive. Dumb cow. Dumb bitch. Belt across my back. I would have really bad bruises on my lower back, back of the arms. If he missed, on my legs,” she said. “My whole back would be covered in blue and purple. Not an inch of skin that you could see that wasn’t bruised, to the point of bleeding.”

Damir was taken away in a paddy wagon. A female police officer said that Jelena denied everything. She says now that her father told her he would kill her if she said anything. She didn’t have the strength to stand up to him.

When the abuse would occur, her mother was often in the next room. “I think deep down I stopped expecting anything from her, stopped expected her to protect me, to say anything. Because it just never came.”

The Bowerys

Former Australian Open champion Lesley Bowery and her husband Bill were around during that time. And Jelena says now that she felt safe with them.

“I never suspected anything, because I never saw anything,” Bowery says in the documentary. “She would say, ‘I walked into a table’. She was so convincing.”

By early 1999, she was crushed by Martina Hingis in the third round of the Australian Open juniors. And Damir “made” Jelena fire Bowery. “He felt like her mentality, her thinking wasn’t good for me, would drag me down because she wanted to sabotage me by making me play juniors,” Dokic said.

But, in reality, Bowery was a threat to his total control.

The late ’90s were a golden age – and a dark age

Remember who was around in the late 1990s – Hingis, Venus and Serena, Kournikova, Pierce, Davenport, Capriati. It was an era when tennis left the little silo it finds itself in these days and went mainstream with stories in entertainment and fashion magazines. And Dokic was good enough to shortly join that high-level group.

At the same time, it was also the start of the toxic culture that persists to this day.

Most of the top players were extremely young, and per the WTA rules were to be accompanied by a parent or guardian. Suddenly, the parental influence got out of control.

In 1999, Dokic qualified at Wimbledon. She met Hingis in the first round of the main draw.

“If I don’t win here … I have to win, if I don’t, what’s going to happen when I get home?” were the thoughts going through Dokic’s head. She crushed Hingis, 6-2, 6-0.

After she lost in three sets to Alexandra Stevenson in the quarterfinals, hell broke loose.

“I got back to the hotel – he made me stand, turn towards the wall, with my hands down, and look down, straight into the wall. This was sometimes the punishment. Sometimes I had to take my clothes off and be just in a sports bra and shorts,” she recalled. “It’s been a great tournament, and it didn’t feel like that. I remember feeling really shitty about that.”

Later, she worked with Aussie legend Tony Roche, who now says, “I had no indication, from my personal experience with Damir, that he was the person that he was.”

Keep your eyes half-closed, and you don’t see it.

She lost 6-1, 6-0 in the first round of the 2000 Australian Open to Rita Kuti Kis.

“Tough one, bad luck”, said Roche.

“He’s too easy going; he’s not tough enough,” said Damir.

Damir made her fire a legend. “I was mortified,” she said.

Drama at Wimbledon

By Wimbledon, with Damir back on the coaching seat, and drinking heavily, everything came to a head.

The WTA was considering banning him. Officials at Wimbledon, it appears, were “willing to give him another chance”. But Dokic defended him in her press conference. She admits now that everything she said in his defence was a lie.

“His abuse of the officials behind the scenes, some other players had noticed some bruising on her body at different times. She was dealing with a lot more than I could comprehend,” said Lindsay Davenport, who was 24 at the time.

Davenport (then No. 1) and Dokic both reached the semifinals. After the 6-4, 6-2 loss – during which Damir exited the court before the end – Dokic was still on the player patio at Wimbledon four hours later. She couldn’t find her parents. Finally, she reached Damir on his phone.

“He’s hammered. He tells me that I’m a disappointment, embarrassing the family, that I should be ashamed of myself, that I’m a loser. And tells me not to come back to the hotel,” Dokic recalled. “But where do I go? He said, ‘I don’t give a shit where you go. But don’t come back to the hotel.’ And he hung up.”

By 11 p.m., a cleaner found her. Tournament referee Alan Mills called her manager, whose agency had a rented house at Wimbledon. She slept there. “I got hold of Damir. By then he’s sobered up a bit. That was really bad, that part. What parent would do that?” her manager at the time recalled.

But no one stepped in.

The Montreal drama

Shortly after Wimbledon, Dokic found herself in Montreal, where she lost to Sabine Appelmans in a third-set tiebreak in the first round of singles.

She was set to team up with countrywoman Rennae Stubbs, who says in the documentary that she had added Montreal specifically to her schedule and had left regular doubles partner Lisa Raymond aside, so she and Dokic could practice ahead of their expected participation in the Sydney Olympics – in their hometown.

But after that singles loss to Appelmans, all hell broke loose again.

“I knew he was going to be angry, just didn’t know how much. We got to the hotel. He was so mad that he goes into the bathroom with me, locks the door, and beat the crap out of me. He slammed my head against the wall multiple times. He was kicking me, my shins were so bruised I couldn’t walk,” Dokic recalled in another emotional moment in the documentary. “He actually punched me in the head, and then I went unconscious for a little bit. He stepped on my head as well.”

Not long after that, Stubbs – 29 at the time – showed up at the door, all fire and brimstone, having heard from someone at the WTA that Dokic might withdraw from the doubles.

She came face to face with a “petrified” Jelena at the door. “I kind of hear Damir in the background, mumbling away like a lunatic. Like he does. So I talked to him,” Stubbs recalled.

Stubbs reiterated to Damir that she had come to the tournament specifically to play doubles with Jelena, and that she expected her to be on the practice court the next morning at 10 a.m.

Having said her piece, she finally mouthed “Are you okay?” to Jelena. “I didn’t say it (out loud), him being an asshole he’d probably turn that around on her,” Stubbs recalled. Jelena just nodded.

The next morning, With Jelena in serious pain from the beating inflicted the night before, her father forced her onto the treadmill. A former WTA employee was on a nearby machine and recalls that Damir was upping the speed of the treadmill – too fast – and that Jelena stumbled off it several times. He then noticed she had marks on her legs.

“I’m thinking at this point, should I say something? Should I get involved? It was tricky – we’d all heard rumours that this was a difficult relationship at times between the two of them,” he said.

In the end, it seemed he did not. No one did.

At 10:03 a.m., Jelena came running to the practice court, where Stubbs was waiting.

“I’m fairly certain I noticed bruising her on her legs. I must have asked four or five times if she was okay. ” ‘No, everything’s fine,’ she said. “What are you going to do? At this point, I was like, ‘this is your burden’, you know what I mean? And that was it.”

The duo lost in a third-set tiebreak to Amanda Coetzer and Lori McNeil. And, indeed, they fell in the second round of the Olympics to Miriam Oremans and Kristie Boogert of the Netherlands.

US Open – more drama

The most public display of Damir Dokic’s temper came at the 2000 US Open, where before Dokic’s second-round match against Oremans, an intoxicated Damir went to the player restaurant.

He was displeased with the size of the piece of salmon. He started yelling about the food, abusing the person behind the desk – she later recalled in a television interview that he called her a “f…ing cow”

Damir was evicted from the site, with Jelena watching on.

Then WTA CEO Bart McGuire – one of those milquetoast, male executives that are too often the norm in women’s sports – recalled she looked “scared, almost haunted. And some of her interviews sounded like hostage videos”.

A six-month suspension

In the end, Damir Dokic was suspended.

“We suspended him for six months. And that six-month ban was carefully calibrated to end just before her 18th birthday,” McGuire said. “Our hope was that when she got to be 18, she’d be able to break free from him on her own, that she’d be able to lead a life separated from him. We felt the longer we could keep him away from Jelena, the better off she would be.”

Perhaps well-intentioned, that now sounds like just another bandaid, a quick fix in the hope that nothing significant or confrontational would have to happen.

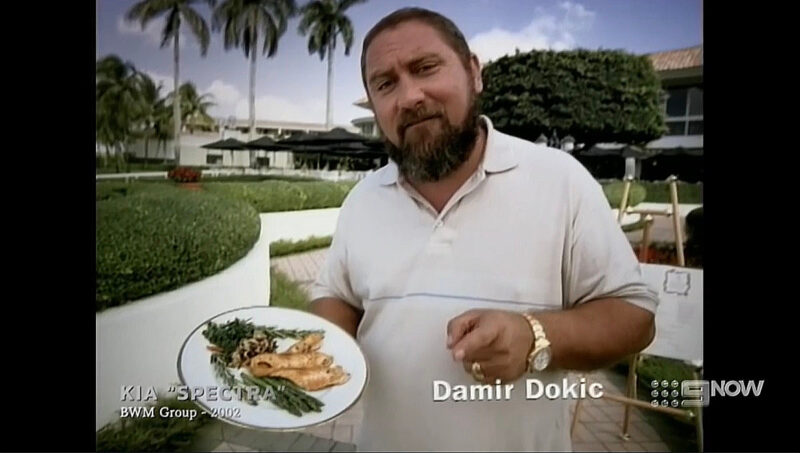

Another irony? Back at home, months later, Australian Open title sponsor Kia actually hired Damir Dokic for a commercial – a spoof on the “small salmon” incident.

It seems incomprehensible now that a major sponsor would be that tone deaf.

“Had we known then what his reputation of being abusive to her was, we wouldn’t do it,” is what a former Kia executive says now.

It’s hard to comprehend how they couldn’t know, how they wouldn’t have stayed far, far away. But it happened.

Whiskey and the Olympics

Paul McNamee, the Australian Open tournament director at the time, was concerned that Damir Dokic was threatening to have his daughter to back and play for Yugoslavia.

More than her personal safety – which seemed a fairly obvious problem at the time – it was a PR problem.

They met.

“We’ve got a PR issue with Jelena if she doesn’t play the Olympics, McNamee said to Damir. “Damir said, ‘You drink whiskey with me, Jelena play Olympics,’ “. So McNamee did. And Dokic played.

It could have been a moment to intervene. It wasn’t. There were other interests at stake.

By January, Damir’s threats to have his daughter represent Yugoslavia were even more public, after she drew Davenport in the first round and Damir accused the tournament of rigging the draw.

“The Aussies fans did NOT appreciate this. Turning her back on what we’ve done for her,” McNamee said.

When she entered Rod Laver Arena and was introduced, she was “booed like crazy”. Damir was sitting at home watching the consequences of his threat, leaving a 17-year-old all alone to deal with it.

Davenport won, 6-3 in the third set. “I remember having zero joy when I won. I didn’t want to answer any questions or talk about it,” Davenport recalled.

“As tennis players you try to forget everything that surrounds everything. But as soon as it over, I think she might have some difficult days ahead, and I wish her the best,” she said in her press conference.

Davenport returned to the locker room after her press conference and saw Dokic sitting on a bench.

And Davenport did the only thing she could really do; she just went to sit with her, and put her arm around her.

“She didn’t say anything, but I didn’t get the sense I should leave. So I kind of sat with her for a little while,” Davenport said.

Dokic recalls that moment, tearfully, in the documentary.

“She was so nice, I was so grateful that she came,” she said.

In her life, there had been so few instances of simple kindness from the outside.

SO much more

The story doesn’t end there. It gets worse, and for so many terrifying years.

She ended up representing Yugoslavia in 2004, then returned “home”.

Dokic ended up signing away all her money – multimillions – to her father, after he found out she was dating F1 driver Enrique Bernoldi.

She thought it would allow her to continue seeing Bernoldi. It did not. She was forbidden.

She split with her family, leaving her younger brother behind.

“It was complicated – a lot of people said she would be funded (by Tennis Australia), would be helped again,” Stubbs recalled. “A lot of people in the industry said she shouldn’t be funded.”

She developed a serious eating disorder that affects her to this day. Depression. Trauma. PTSD.

Dokic tried to come back – and she had a great moment out of nowhere in 2009 when she won four straight three-set matches and made the quarterfinals at the Australian Open, where she lost to Dinara Safina in three sets.

She kept trying. For a few years.

And she began to talk about it more. Finally.

Nobody did anything

The Jelena Dokic story was a story everyone knew – or at least, bits and pieces of it, enough to be concerned.

But no one did, or could do, anything to stop it.

The question – and the same question persists in 2024 – is this: should they have? Could they? How do you intervene in a player’s personal relationships? Especially if the player is too frightened to come forward?

Some of the people in the documentary – notably the Bowerys, and Dokic’s final coach Louise Pleming – come across as devastated they didn’t know enough, couldn’t do more.

Others, not so much. Too many essentially seemed to feel that it wasn’t their problem, and there wasn’t much they could do.

Pam Shriver: “How could Tennis Australia, how could the WTA, how could the sport just have brushed it off as an angry, aggressive dad? Didn’t they know enough that abuse was going on, not to investigate further?”

The WTA’s Brenda Perry, an Aussie: “Damir Dokic is the only person I’ve ever been afraid of in 30 years, over 50 countries, over 1,000 tournaments.”

Tennis Australia statement, Nov. 2017: “There were many concerned for Jelena’s welfare, many who tried to assist with what was a difficult family situation. Some officials went even as far as lodging police complaints, which, without cooperation of those directly involved, unfortunately could not be fully investigated.”

Current AO tournament director Craig Tiley: “Back then our resources were limited. 20 years later, there would have been a faster response, And unacceptability of that type of behaviour.”

Former WTA CEO McGuire: “We did what we could, sort of around the edges. But we couldn’t – beyond making sure that Damir didn’t show up at our tournaments – we couldn’t take Jelena out of Damir’s hands.”

Davenport: “It’s clear that nothing was probably done by any entity – from the WTA, agents, companies sponsoring her. Even for us the players, it was hard to really fathom what she was really going through, because she didn’t talk to anybody.”

At the 2022 US Open, WTA player council member Victoria Azarenka weighed in on the subject.

“Sensitive subject, you won’t hear those stories unless players come out. It happens right and left on the tour, which is unfortunate. Our job is to be better at safeguarding. As player council, it’s almost (the) no. 1 subject to us. Because we see those vulnerable young ladies that are getting taking advantage of in different situations. It’s really sad. It really makes me emotional.”

Fast forward to 2024, even with a new safeguarding protocol, has anything really changed?

Unbreakable was truly shocking to watch and listen to. The total lack of compassion and support of a young girl being knowingly and emotionally abused is staggering. The tennis authorities seemed only interested in their own image. Those who saw the abuse take place are as bad as the abuser. Shame, shame, shame, my heart goes out to Jelena I was truly triggered on hearing her story. I hope now Jelena you have found peace and happiness after enduring such pain and suffering. I commend you for your bravery in telling your story. Sending you much love light and hope for the fut.

After having watched the recent documentary and having already read the book Unbreakable, I was really distressed and dismayed that Jelena couldn’t be saved from this most awful man. How she suffered,how could people around her let this happen?

I wish somebody would’ve had the guts to stand up to this most obnoxious creep.Had he been my father,I would have wanted to kill him and then fully expect NO punishment for what he put me through.

He’s also a criminal for taking all of her prize money and I believe he has never been punished for anything he did to Jelena.If there is one good thing that has come from it ,it is this,the whole world now knows what a despicable,spiteful,horrible human being this man is.

I hope,in his quieter moments that he can reflect on his actions and behaviour and should feel thoroughly ashamed of himself.It is too much to hope for that he would ever have it within him to ever apologise to Jelena.

I would love to knock on the front door of his mansion(paid for, by the way,with Jelena’s blood,sweat and tears )and punch him squarely in his stupid face.

He should be thoroughly,thoroughly ashamed of himself,that man.Also,how about repaying all of the money that you took from Jelena,you bastard!

Somehow,someway,somewhere,you,Damir Dokic ,are going to pay dearly for your sins.Karma’s a bitch.

I found the doc on Youtube. I haven’t watched it yet, but, read some of the comments. Unbelievably, quite a few people sided with her father! They think she played her best tennis when he was coaching her, so obviously his methods worked, & that he only wanted what was best for her. Somehow, humiliating & beating the crap out of her was justified. Have people lost all their common sense & humanity!? I remember when she was playing, & the rumours that were going around. I agree it was so sad that no one could, or, did anything. And, as you wrote, even sadder that it is still going on. Re. Rybakina , I am thinking maybe she does not not know what constitutes abuse. Maybe she is just so used to it that it is normal for her. Hopefully, not another tragedy in the making.

Was it the same doc? I don’t remember anybody really saying that in this one.

(Ah yes, I see that someone illegally uploaded it).

Wow. That’s awful. Thanks for the report, Steph.