–

The issue of the abuse of young girls and women in tennis is an ongoing one. It’s not just sexual abuse; it’s emotional abuse and control – and everything in between.

And it has been brought to the fore again this week by two coincidental, but concurrent events.

First, the memoir by former world No. 4 Jelena Dokic has been made into a heartbreaking documentary, which aired his week in Australia – two days after the end of the Australian Open.

And former top French player Isabelle Demongeot, whose seminal memoir back in 2007 opened the floodgates – particularly in France – and shone a terrifying light on the issue of abusive coaches as God-like figures and how difficult it is to get justice – is coming out with an updated version this month.

Here’s a recap of the Dokic documentary.

Demongeot updates harrowing memoir

The updated version of Demongeot’s 2007 memoir, with five additional chapters, will be released Feb. 24. And Demongeot’s story of nine years of rape and terror at the hands of coach Régis de Camaret beginning at age 13 has tragically not served as a wakeup call it should have been.

By the time Demongeot was ready to talk about it and reclaim her life, the statute of limitations had run out on prosecuting de Camaret – a revered coaching guru who worked with many other young French female players. But she dug in. And after finding 26 other girls who’d been similarly abused between 1977 and 1989, they were able to prosecute de Camaret on several accusations for which the statute of limitations had not expired.

In 2012, de Camaret received an eight-year sentence for rapes and attempted rapes on two minor girls. In 2014, on appeal, the sentence was increased to 10 years; he was released in Aug. 2019.

So many cases, just the tip of the iceberg

In 2022, former top-40 pro Fiona Ferro took her former coach, Pierre Bouteyre, to court for rape and sexual assaults that occurred between the ages of 15 and 18. That one is still making its way through the system, two years later; Geddes, a former coach of Alizé Cornet, claims it was a “love story”.

Earlier that year, American player Kylie McKenzie filed a lawsuit accusing USTA coach Anibal Aranda of touching her inappropriately at the USTA’s national centre in Orlando, Fla. She was 19 at the time; Aranda (also the former coach of now-retired young player Cici Bellis) was 34. McKenzie was awarded $9 million US; the case is under appeal.

In 2023 another former pro, Tunisia’s Selima Sfar – long before Ons Jabeur, she was the first Arab woman to make the top 100 in the WTA rankings – accused de Camaret of abusing her when she was 12 years old and a long way from home.

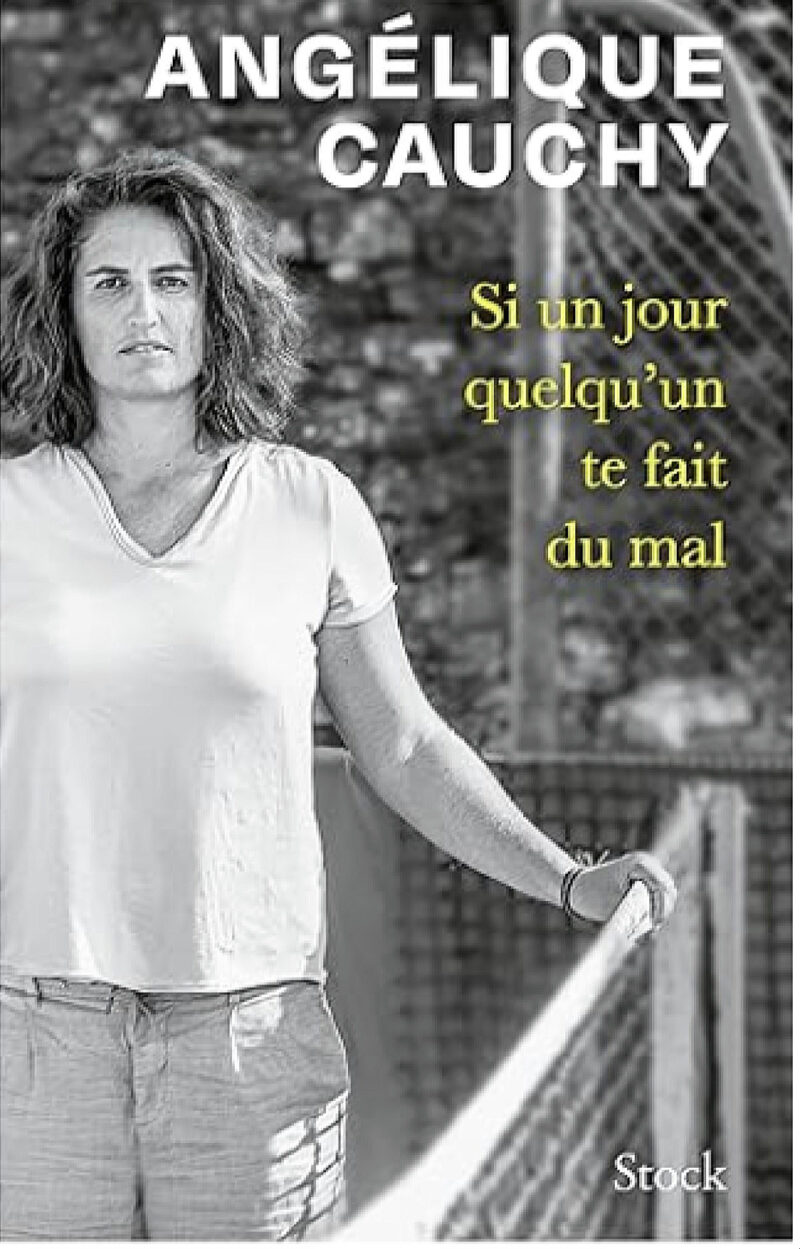

In 2024, former French player Angelique Cauchy watched her former coach Andrew Geddes – who she accused of raping her for a two-year period beginning when she was 12, be sentenced to 18 years in prison. She, too wrote a memoir that came out last month.

Also last month, the Athletic published a story about Caroline Ullring and Karen Clark, two players accused her college coach of sexually assaulting them – more than 25 years apart.

Decades later, the problem persists

If there’s a theme to the cases noted above – and so many more that either didn’t get the same attention, or have never come to public light at all – it’s that there’s no specific age.

From prepubescent girls to young adults, the theme of male dominance and control, of the coach as the “queen maker” who instills fear in girls, young women – and their families eager to taste success – doesn’t change much.

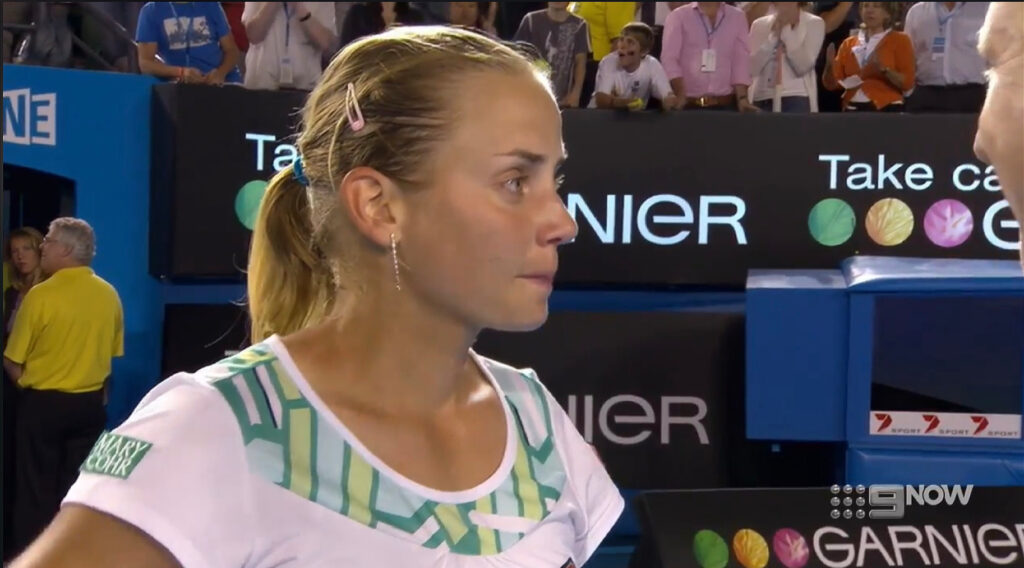

But these two landmark cases of abuse of young women in tennis (and no, we’re not forgetting that many boys are also abused) are coming to the fore again at the end of a tournament marked by the ongoing drama involving top player Elena Rybakina and her former (and future?) coach, Stefano Vukov.

Rybakina is 25 now. But she was 19 when she began working with Vukov, who was then 32.

The pair combined to bring the introverted Russian, who now represents Kazakhstan, to the very top of the game – culminating with her Wimbledon title in 2022.

In the last year or more, it’s gotten complicated as numerous observers (including yours truly) have noted the way Vukov treats her publicly – during matches, on the practice court.

(And yes, it’s a total oxymoron in tennis that young adults pay older men to treat them that way).

Those of us who did speak up – most notably former player Pam Shriver, who only recently recounted the story of her abuse as a teenager by her coach, who was then 50 – were criticized for not minding our own business. Or not knowing what we were talking about.

In a statement that was published on her Instagram account at the time – at the Australian Open two years ago – Rybakina strenously denied she was being mistreated. But fast forward to just before last year’s US Open, and Vukov was … suddenly out of the picture. For more than a year, Rybakina had retired or withdrawn from tournaments with various injuries and illnesses. Her once-promising career seemed in a bit of a fragile state.

In November, Rybakina hired notable former player Goran Ivanisevic, like Vukov a Croat, to start the next chapter in her career. “I just wish him the best in his new chapter,” she said of Vukov.

Except …

A rare public coaching suspension

In early January, Rybakina announced that Vukov was once again “part of her team”. Except for one problem. As the Athletic reported and the WTA confirmed, Vukov had been suspended by the WTA Tour. He could go on site at the Australian Open, but he’d have to buy a ticket like any other fan. He was not to be credentialed at any event.

“The WTA can confirm that Stefano Vukov is currently under a provisional suspension pending an independent investigation into a potential breach of the WTA Code of Conduct,” was the statement from the WTA given to The Athletic.

It can’t be emphasized enough that this kind of confirmation is extremely unusual from the usually opaque WTA.

The Athletic story describes Rybakina’s months-long lobbying of the WTA to allow Vukov to coach her.

It seems Ivanisevic might not have been in the loop on this, at least not if you read what he told Ben Rothenberg. Amid the uncertainty, Rybakina reached the round of 16 with a very good draw; she lost in three sets to Madison Keys – who as we know, went on to win the tournament.

And then, as quickly as it came, Ivanisevic announced on his Instagram that their association for 2025 (at least as described in the WTA website story linked to above) was really “only a trial”. And that it was over.

At least two other coaches suspended

The WTA’s investigation, per the Athletic, was supposed to be complete by the end of the Australian Open. There has been no news to that effect. But the publication did state that the WTA issued a new 50-page safeguarding document in late December that gives the WTA the power to “to provisionally ban a coach without an explanation or notice of an ongoing investigation.”

Prior to that document being published, at least two other coaches havd been issued suspensions. One Open Court can confirm directly; the second suspension, we have on very good authority.

One of those coaches has worked with multiple WTA players. Both are currently back working. There are various hoops to jump through, notably some online education classes and, of course, no further complaints.

There’s a certain level of sympathy for the situation the WTA finds itself in. In most cases, at their level, they’re dealing with adults, women who have reached the age of majority. And in some of those cases, they’re dealing with tennis fathers – a complicated family dynamic that makes it even more difficult for a player to come forward and ask for help.

The other factor is that the players are not WTA employees. They are independant contractors; the level of control they can exert over whom those contractors choose to have in their entourage is debatable, at best. And quite possibly a tricky area legally.

But it appears they at least have been trying.

The Dokic and Demongeot cases should have served as cautionary tales – wakeup calls to the tour, and notably to national federations and to anyone who is around the young players, that the vigilance needs to go above and beyond to ensure that young women aren’t forever scarred by their tennis experience, once their brief (relatively speaking) careers are over.

But two decades later, the issues remain the same. Even worse, perhaps, because there is so much more money in play now.

Whether or not the efforts have any effect on Rybakina and Vukov might well stay under wraps – until, or if, he shows up on the practice court with her at a tournament on the upcoming Middle East swing.

But, at the very least, everyone will be watching.

More Stories

Canucks This Week – Week ending Oct. 17, 2025

WTA Rankings Report – As of Oct. 6, 2025

Canucks This Week – Week ending Oct. 12, 2025 (Friday results)